In early July, British investment bank Barclays PLC announced a surprise settlement with agencies from the United States and Europe and admitted that, for years, it had been reporting false information to the British Bankers’ Association as part of the process of determining the London Inter Bank Overnight Rate (LIBOR)—a key metric used as the basis for trillions of dollars’ worth of other financial products, including some commercial real estate debt. The bank agreed to pay more than $450 million in fines: $200 million to the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission, $160 million to the criminal division of the U.S. Department of Justice and $92.8 million to Britain’s Financial Services Authority.As a result of the scandal, key executives—including Barclays Chairman Marcus Agius and Barclays CEO Robert Diamond—announced their resignations. The bank is now fighting to regain the trust of investors, borrowers, other banks and regulatory agencies in the wake of the revelations.And, allegedly, it wasn’t alone. More than a dozen other banks remain under investigation by European and U.S. financial regulatory bodies for doing the same thing as Barclays. More fines may be handed down. And they are likely to be heftier than what Barclays paid since agencies went easy on the British bank for being the first institution to step forward and admit to wrongdoing.The scandal has also triggered dozens of lawsuits as community banks, borrowers, investors and municipalities affected by LIBOR try to recoup potential losses that resulted from inaccuracies in the reported rates. For example, entities including Charles Schwab and the City of Baltimore filed suits against the banks that submit LIBOR rates accusing them of price fixing, under the Sherman Antitrust Act.The docket has gotten so full, in fact, that U.S. District Judge Naomi Reice Buchwald in early August suspended several new lawsuits until the outcomes of the many lawsuits in progress had been determined.Overall, it is estimated that up to $800 trillion in loans, swap arrangements, derivatives and other financial contracts are based on LIBOR. So changes in the rate—as well as its manipulation—have massive potential knock-on effects for a wide variety of institutions.The scandal has died down some since the initial firestorm early this summer. But it threatens to flare back up, depending on the results of the investigations and negotiations still taking place.There were two phases to Barclays’ duplicity. Barclays admitted to reporting the rate higher prior to 2008 in order to improve its position on some derivatives contracts. In this phase, it’s possible that borrowers that placed loans on LIBOR were paying higher interest rates than what should have been available while lenders benefited.Barclays admitted to reporting lower rates after the financial crisis. This primarily would have benefited borrowers and hurt smaller lenders that looked to LIBOR as the benchmark on which to base interest rates.There are direct implications for the commercial real estate sector.LIBOR is commonly used to set the rates for construction loans, floating rate bridge loans and two-, three- and five-year mini-perm loans. Loans are priced at a spread to LIBOR itself.So manipulation of LIBOR means that loans done during the past decade may have been mispriced, depending on the extent that LIBOR was distorted. Barclays alone couldn’t have shifted the rate that much. But if more banks were doing the same thing, rates may have been off significantly.LIBOR was also used by conduit lenders for floating rate loans. This largely affects legacy issues since overall CMBS issuance remains low today. But here too borrowers probably benefited. If anyone got cheated it was investors at the back end that may have gotten lower returns on their investment than if LIBOR had not been manipulated.

Still, analysts don’t believe the CMBS sector has been affected that greatly by the situation.

“‘The current LIBOR controversy does not effect CMBS defaults, losses or ratings, given significant interest rate stresses assumed in our analysis. Plus only a small portion of CMBS are floaters,” says Dan Chambers, managing director with rating agency Fitch.

Borrowers have “enjoyed record low, dirt cheap rates,” says Mark Scott, founder and principal of Commercial Mortgage Capital Corp. “But you have to believe that lenders are going to be upset regarding the fact that they were undercharging customers. They could have been getting a greater yield had LIBOR not been manipulated.”

What happens next is anyone’s guess. In the worst case scenario—LIBOR being scuppered entirely—existing loans and new loans would have to be set to a new index. That process could be drawn out and at least temporarily slow the volume of lending until new standards are agreed upon.

To date, however, the worst case appears unlikely. Banks and borrowers have shown no desire to shift away from LIBOR. And while there have been calls to reform how the number is determined to add greater transparency to the process, there are few, for now, calling for it to be eliminated entirely.

In the commercial real estate sector, lenders continue to originate construction and bridge loans based on LIBOR and volume has not been affected since the scandal broke out.

For example, in late August, Prime Group Realty Trust refinanced its 330 North Wabash Avenue property in Chicago with the proceeds of a $200 million first mortgage loan from Landesbank Hessen-Thuringen Girozentrale and New York Life Insurance Co. The loan consists of a $111.9 million initial advance to repay the existing first mortgage loan on the property and $88.1 million in subsequent advances for tenant and capital improvements. The interest rate on the loan is 30-day LIBOR plus 2.85 percent.

The process

At the heart of the issue is the way LIBOR is determined. The rate is set by a panel of 18 banks that report daily estimates of what interest rate they think they would need to pay to borrow money for three months from other banks. The top four and bottom four estimates are discarded, and that day’s LIBOR rate is the average of the remaining 10 rates.

However, the numbers aren’t based on actual transactions—they’re estimates. So there’s no way to check their accuracy. In fact, the money center banks have largely stopped borrowing from each other since 2008. Instead, they do most of their interbank borrowing directly from central banks where interest rates close to 0 percent remain available. What that means is that LIBOR has become a theoretical measure rather than an index of actual market activity.

Moreover, banks have a massive incentive to lie about what the rates are for various reasons.

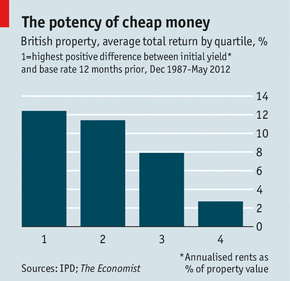

According to the British news magazine The Economist, “[E]ven relatively small moves in the final value of LIBOR could have resulted in daily profits or losses worth millions of dollars [on these investments]. In 2007, for instance, the loss (or gain) that Barclays stood to make from normal moves in interest rates over any given day was £20 million ($40 million at the time).”

In the wake of the financial crisis LIBOR took on another meaning: it became a proxy for the health of the major financial institutions. Those reporting higher LIBOR rates were seen as weaker. Therefore, banks had an incentive to report lower rates to signal to investors that they remained solvent and stable.

Richard K. Green, director of the University of Southern California Lusk Center for Real Estate, has been attempting to create a model to determine whether banks would be more likely to over- or underreport LIBOR given different market conditions.

The overall premise is that every bank would lie in order to improve their position. But because banks, depending on different scenarios, could find it fortuitous to report both higher and lower rates, it’s difficult to determine exactly how LIBOR is likely to be distorted.

“The outcome of gaming is not at all clear,” Green says. “Weak banks have an incentive to say a low number, so they can borrow at low rates. Strong banks have an incentive to say a high number, so they can lend at higher values.”

Green plans to continue to develop the model and try to determine how the gaming of LIBOR ultimately affects borrowers, including commercial real estate investors.

What has happened

So far, the commercial real estate sector seems immune from any potential deleterious effects of the LIBOR scandal.

Commercial and multifamily mortgage origination volumes during the second quarter of 2012 were up 25 percent from second quarter 2011 levels, and up 39 percent from the first quarter of 2012, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association’s (MBA) Quarterly Survey of Commercial/Multifamily Mortgage Bankers Originations. Anecdotally, lenders and intermediaries are reporting that activity has remained healthy throughout the summer, even after the news about LIBOR broke.

The MBA index does not include construction loans. But indications are that originations have not slowed in that area of the market either.

“We have not seen a slowdown in the momentum in construction lending,” says Sam Chandan, president and chief economist of real estate and economics analysis firm Chandan Economics. The firm tracks loan volumes and activity nationwide.

Moreover, some experts argue that even if LIBOR was distorted the effects were likely too small to have hurt borrowers dramatically.

“It seems minimal in how it may impact commercial real estate and quite frankly, it’s unquantifiable,” says William E. Hughes, a senior vice president and managing director of Marcus & Millichap Capital Corp. “You get an interest rate, you’re floating it 300 over LIBOR, but the fact of the matter is there is little impact if LIBOR was a few basis points higher or lower than it should have been. … I’m not sure you can effectively quantify the impact in a transaction unless it’s an ultra-large transaction or ultra-large client.”

But it may not have affected borrowers at all, Hughes argues.

“If banks conspired to increase LIBOR, correspondingly, they could have been adjusting spreads down. Or if rates were down, spreads may have been up. So the all-in rate may not have been affected at all,” he says.

One sign that the sector has not sweated the LIBOR situation that much is the fact that it seems no commercial real estate firms are involved in the myriad lawsuits that have been launched in recent months. None of the sources interviewed for this article could name an example of a commercial real estate borrower joining a potential class action lawsuit.

The implications

Part of what’s at play is that borrowers in the commercial real estate sector don’t look that deeply into how LIBOR is determined. They engage the measure more passively.

“We line up at the pump and pay the price there and shop around for the best deal,” says Jeffrey Weidell, president of Northmarq Capital LLC, a financial intermediary. “The cynic in me says LIBOR is like a sausage. Nobody wants to know how it gets made. … It is probably always manipulated. But as long as the rate is low, borrowers are ultimately satisfied.”

That means the biggest challenges for the commercial real estate sector would only emerge if LIBOR ceases to exist. At this stage, that seems unlikely. Replacing LIBOR would be extremely disruptive because of the number of derivatives contracts that would have to be rewritten. The financial industry would like to avoid this. Instead, the United Kingdom’s Financial Services Authority is developing recommendations for how to overhaul LIBOR to make it more transparent and allow it to retain its position as a major benchmark for other interest rates. The authority has issued a 58-page paper outlining some potential reforms and discussions are expected to continue throughout the fall on the potential changes.

Still, if LIBOR were to be dumped, there are several scenarios in how it could be replaced.

One idea that’s being floated is a hybrid system in which banks would continue to give estimates of their borrowing costs, but also mandate that the numbers include some documentation as to how the estimate was reached or examples of actual transactions.

“I think it’s not going to shake things up, unless there’s some massive overhaul and the elimination of LIBOR,” says David Pascale, senior vice president with George Smith Partners, a real estate investment banking firm. “The market would become volatile unless it was telegraphed well in advance and it was orderly.”

Many loan documents do outline specific conditions of what happens if LIBOR ceases to exist, says Scott. The rate will be reset according to a rate based on U.S. Treasuries reported two days prior to the rate lock.

However, other documents are more vague on what will happen if LIBOR is discontinued.

“In some documents, it says if LIBOR goes away that we will come up with a new index. But it doesn’t say how,” Weidell says. “If that happens, there will be scrambling.”

The replacement index for LIBOR doesn’t necessarily need to be in the same interest rate range as LIBOR itself. After briefly spiking in late 2008 and early 2009, one-month LIBOR has generally been less than 0.30 percent since. Three-month LIBOR has been about 20 basis points greater and six-month LIBOR has been about 50 basis points greater.

The replacement index could be a higher base. But the spread could be tightened. That would leave the all-in rates for borrowers on loans virtually the same as they are.

Two likely possibilities are that the finance sector would turn either to short-dated Treasuries or the corporate bond market. “The likelihood that we’d see the reliance on a benchmark that is more esoteric than that is very low right now,” Chandan says.

Another possibility would be the prime lending rate, which runs approximately 300 basis points above the federal funds rate determined by the Federal Reserve Bank.

However, such a shift may not be as disruptive as it sounds.

“The use of LIBOR as a benchmark is in part a reflection of the indices being fairly well embedded,” Chandan says. “But that doesn’t mean we haven’t developed alternative benchmarks that are more transparent and calculated in a way that is market based.”

Ultimately, the most serious outcome of the LIBOR situation may not be the direct effects. Instead, the problem is that it adds further uncertainty to capital markets that still have not fully recovered from the 2008 financial crisis.

“It’s more anxiety and uncertainty in a market that has very slowly been trying to find its footing,” Scott says. “The commercial real estate lending market has been soft over the past three years. … It’s just starting to feel its way out of the dark. This isn’t earth shattering, but it is a cause for pause.”

Further development of the LIBOR scandal could shake up capital markets because of the sheer volume of financial products it affects. The sorting out of trillions in derivatives contracts, for example, could eat up time and resources and end up slowing the pace of lending again.

“It would cause investors to be risk averse and be bad for credit markets,” Pascale says.

Another cause for concern is that the LIBOR scandal is another black eye for the financial services industry, which could increase the calls for further regulation. That, in turn, may have unintended consequences for the commercial real estate sector by making capital more expensive and harder to come by.

“We have all this talk of more control, more government intervention, more oversight and that could lead to more restriction and less of an open market world in which we live,” Hughes says. “I think therein lies the biggest potential risk.”